Venus is unique among the Sun’s planets in having a day longer than its year – that is it turns so slowly it takes longer to rotate on its axis than it does to orbit the Sun. This strange behavior is probably a consequence of its thick atmosphere, a case of the tail wagging the planetary dog. Unusual as this is within the Solar System, it may be quite common elsewhere.

Many of the Solar System’s moons, including our own, have a rotation period that matches their orbit, causing them to always keep the same face to their planet. The same forces that induce this so-called “tidal locking” apply to planets in close-in orbits. It was once thought Mercury would be tidally locked to the Sun, with one burning hot side, and another cooled by facing forever outwards towards the stars.

Yet according to Professor Stephen Kane of the University of California, Riverside it is Venus that nearly ended up with two such differing sides, and only its thick atmosphere prevented such an outcome. Kane presents his case in Nature Astronomy, along with its implications for newly discovered planets.

The Venusian year is 225 Earth days long, but it takes the planet 243 days to rotate.

Yet not everything moves so slowly there. The winds on Venus are so fast much of the atmosphere takes less than four days to complete a circuit of the planet, driven by heat imbalances between day and night. They drag at the planet’s rough surface and slow its already ponderous rotation further, and Kane considers them the reason the two periods don’t match.

“We think of the atmosphere as a thin, almost separate layer on top of a planet that has minimal interaction with the solid planet,” Kane said in a statement. “Venus’ powerful atmosphere teaches us that it’s a much more integrated part of the planet that affects absolutely everything, even how fast the planet rotates.”

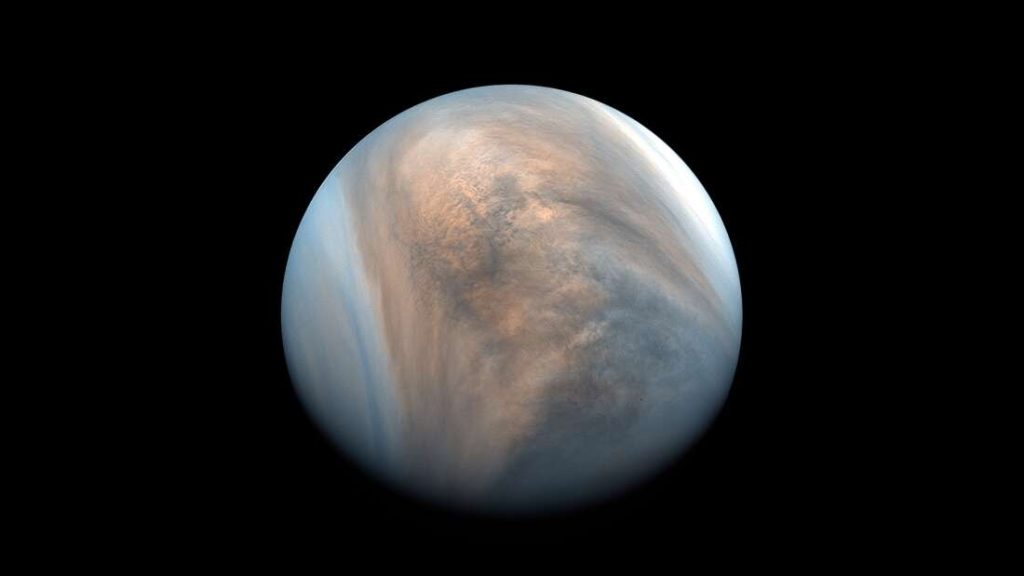

Venus’s thick atmosphere of almost pure carbon dioxide is more famous for absorbing the Sun’s heat very effectively, making the planet hotter even than Mercury and confounding science fiction writers who imagined a humid but habitable climate.

The question Kane poses is whether these two effects are related: has the length of Venus’s day contributed to its extreme average heat and move away from habitability? The answer could have important implications for what we can expect to find on rocky planets that orbit near the inner edge of stars’ supposed habitable zones.

With so many planets now being found close to their stars, choices have to be made about which are priorities to study with limited telescope time. Decisions will depend on models of likely conditions. “Venus is our opportunity to get these models correct, so we can properly understand the surface environments of planets around other stars,” Kane said. “We aren’t doing a good job of considering this right now. We’re mostly using Earth-type models to interpret the properties of exoplanets. Venus is waving both arms around saying, ‘look over here!”

If even this seems rather distant from challenges on Earth, Kane points out understanding Venus’s atmosphere better could teach us about our own. This has happened once already; one of the things that alerted scientists to the dangers of a runaway greenhouse effect was seeing just how hot – 500ºC (900ºF) – Venus had become despite much less sunlight than Mercury.

Related article:

There May Be A Fast Way To Observe This Never-Before-Seen Quantum Effect

Time Travel Could Be Possible, But Only With Parallel Timelines