The concept of microplastics (MP) was proposed as early as 2004 by Richard Thompson of the University of Plymouth in his landmark paper “Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic?” Subsequently, it has received significant attention from all walks of life due to its widespread presence in the terrestrial systems. Globally, plastic production reached 368 million tons in 2019 with 51% production in Asia and China alone contributed about one third (31%) of the global plastic production.

Human beings throw plastic waste into the environment, and the environment repays it with microplastics. This “retribution” is right in front of us as microplastics are everywhere worldwide. They are far away from the sky: as far as the rare Antarctic ice sheet, as deep as the Mariana Trench at the deepest part of the earth, and as high as Mount. These microplastic pose serious concerns regarding biota and further aggravate the climate change.

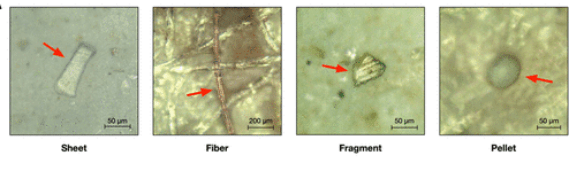

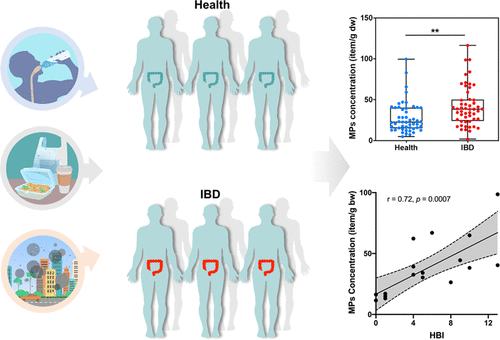

Plastic can be digested in human body and excreted through the gastrointestinal tract with the biliary tract. However, it may not be as harmless as we assumed earlier. Recent animal studies documented that microplastics of less than 10 μm can pass through the cell membrane into the circulatory system and reach other tissues. Furthermore, a study published in Environmental Science & Technology reported that the fecal MP concentration in IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) patients (41.8 items/g dm) was significantly higher than that in healthy people (28.0 items/g dm). By investigating fecal samples from 11 provinces and cities in China, the team found alarming evidences: Participants who often drink bottled water, eat takeaway food, and work in nature are more prone to plastic. Higher content of microplastics in their feces, positively correlates with IBD status and suggests that MP exposure may be related to the disease processes.

Moreover, microplastics may have penetrated in various organs of the body. A latest study published in Environmental International found microplastics in human blood, which further raised serious concerns about the long-term impact of microplastics on human health. In this new study, researchers recruited 22 healthy volunteers to obtain blood samples through intravenous puncture.

After eliminating the possibility of contamination of blood samples, they detected quantifiable microplastics in blood of 17 people (77%), with an average of 1.6 micrograms per milliliter of blood. The most common detected plastics were polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP) and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). In detail, PET, PS, and PE accounted for 50%, 36%, and 23% of the plastics found in blood samples, respectively.

PET is usually used in mineral water bottles, beverage bottles and various household appliances; PS is widely used in food packaging materials; PE is used for packaging films and plastic bags; PP is widely used in takeaway lunch boxes; and PMMA is mostly used in the appearance of electronic equipment and lighting equipment. However, the microplastic accumulation time period in the blood is still unknown, so their fate in the human body needs further investigations. Scientifically, it is understandable that microplastics may reach all organs of the body through the circulation system.

Dr. Muhammad Adeel, who is working on Environmental pollution at Beijing Normal university, Zhuhai (who did not participate in the study), said: “These are alarming reports because microplastics have been proven to cause inflammation and cell damage under experimental conditions. Recent studies proves that microplastics are not only permeated in the whole environment, but also in our bodies. The long-term consequences of this situation are still remained unclear and needed serious attentions from all stakeholders.”

If the microplastics in the blood are indeed carried by immune cells, then the serious question arises about correlation with other diseases. Will this exposure potentially affect immune regulation or susceptibility to immune diseases? All these questions demand further research.

Reference

Yan, Zehua, et al. “Analysis of Microplastics in Human Feces Reveals a Correlation between Fecal Microplastics and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Status.” Environmental science & technology (2021).

Leslie HA, Van Velzen MJ, Brandsma SH, Vethaak D, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Lamoree MH. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environment International. 2022 Mar 24:107199.