Health officials in Wisconsin are investigating what may be the second death in the mysterious outbreak of childhood hepatitis spreading across the world recently.

The case is one of “at least four … among children in Wisconsin,” the state’s Department of Health announced Wednesday, all of whom “had severe outcomes.” One child required a liver transplant and another died, the health alert noted.

Cases of childhood hepatitis – the medical term for inflammation of the liver – have now been reported in more than a dozen countries, with Japan being the most recent nation to confirm its presence.

While hepatitis is not unheard of in children, experts are concerned about the severity and spread of the current outbreak.

“Mild hepatitis is very common in children following a range of viral infections, but what is being seen at the moment is quite different,” said Graham Cooke, NIHR Research Professor of Infectious Diseases at Imperial College London. “Children are experiencing more severe inflammation, in a few cases leading the liver to fail and require transplantation.”

If the Wisconsin cases are indeed connected to the larger outbreak, the illness will have resulted in the deaths of at least two children and left many more with severe outcomes rarely seen in healthy kids. In the UK, where the majority of the world’s 160-plus cases reported have so far been found, around one in every eleven cases has required a liver transplant.

While the cause of the outbreaks is yet to be uncovered, one leading hypothesis points to a type of adenovirus – specifically, adenovirus 41 – as a likely culprit. Usually, this virus is little more than a tummy bug in children and isn’t commonly associated with hepatitis at all, so the fact that more than three-quarters of UK cases tested positive for the strain is something that raises its own questions.

“There are very few case reports in the global literature of adenovirus infection being associated with hepatitis in immunocompetent children (or adults) – so if it transpires that adenoviral infection is involved in causing this disease outbreak, there will be a need to explain why the natural history of adenovirus infection has changed so dramatically in 2022,” noted Will Irving, Professor of Virology at the University of Nottingham.

“However, the increasing percentage of children fulfilling the current case definition of severe acute hepatitis in whom Ad-41 has been found cannot be ignored, and suggests that Ad-41 infection may well be linked in some way with the disease,” he said.

With these new cases under investigation, Wisconsin joins at least seven US states that have seen outbreaks of unexplained hepatitis in children. While the international alarm was first sounded by the UK earlier this month, some of the earliest case reports were later found to have turned up in Alabama as far back as October 2021, and all nine were found to also be positive for adenovirus.

With that in mind, the Wisconsin announcement repeats recent CDC advice that clinicians finding hepatitis in children without a known cause should consider also testing for adenovirus.

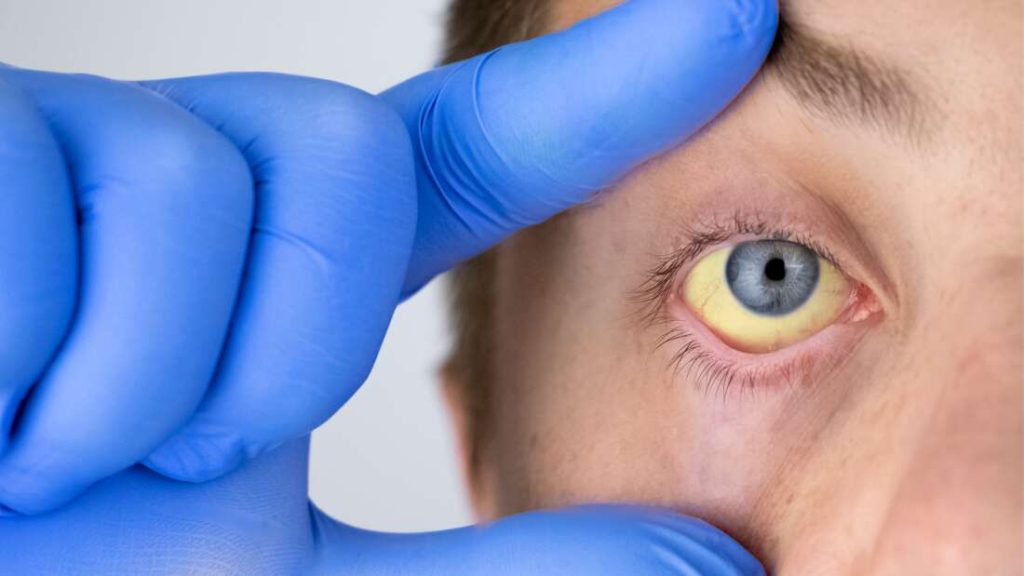

Meanwhile, health authorities across the world are reminding the public to stay alert for the signs and symptoms of hepatitis, which can include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, light-colored stools, joint pain, and jaundice (yellow skin and eyeballs).

“We encourage parents and caregivers to be aware of the symptoms of hepatitis, and to contact their healthcare provider with any concerns,” the CDC advised. “We continue to recommend children be up to date on all their vaccinations, and that parents and caregivers of young children take the same everyday preventive actions that we recommend for everyone, including washing hands often, avoiding people who are sick, covering coughs and sneezes, and avoiding touching the eyes, nose or mouth.”

Related article:

Scientists identify optimal amount of sleep to get in middle to old age